This article first appeared on SpyTalk.

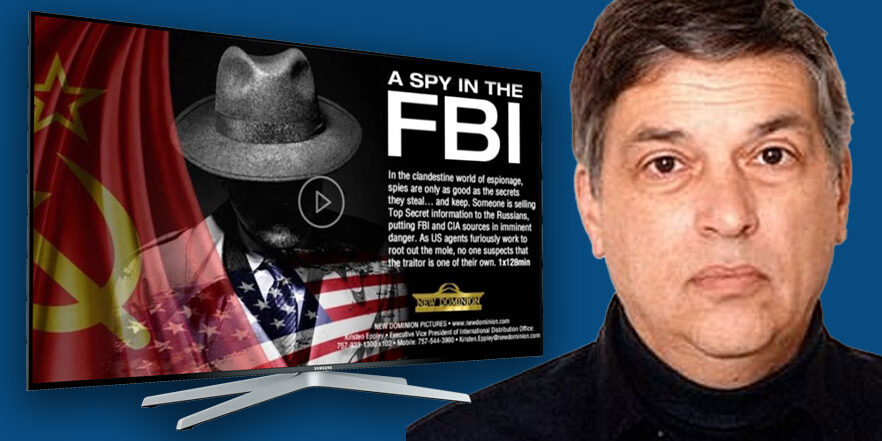

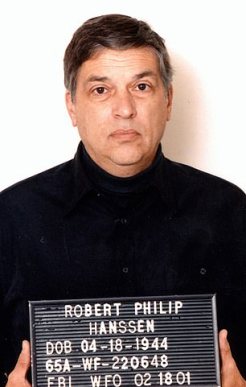

I’m the psychiatrist who met with turncoat FBI agent Robert Hanssen for a whole year after he went to jail in 2001, sentenced to life for spying for the Russians. For years I’ve specialized in the psychology of so-called insider spies, alongside my day job as a psychiatrist with a security clearance to treat intelligence community personnel. And that’s how I came to be interviewed, along with many others who knew Hanssen, for “A Spy in the FBI,” a two-hour special on the Reelz cable channel. The show dropped on February 14, Valentine’s Day, and while I watched the finished product, it was not without conflict for me.

Doing so violated my personal rule of not reading or watching anything about the story of Robert Hanssen except what I already knew myself from my meetings with him. I took the position of wanting to preserve as pristine my own impressions and memories of the time I spent interviewing Hanssen at the Alexandria, Va. Detention Center—altogether nearly 100 hours over a full year—before he was shipped off to the supermax prison in Florence, Colo., for the rest of his life. I was afraid that if I took in information from other sources, I might unwittingly absorb details that would contaminate what I knew from my primary source, Hanssen himself.

I always felt that my main objective was to capture the personality of Hanssen, now nearly 77, as he chose to reveal it, and of course, to pick up on other facets of his life that might emerge whether or not he meant to let them show.

And, yes, from watching “A Spy in the FBI,” I did learn various details that I didn’t know before.

The Many Faces of Bob

Let me start by highlighting the main psychological feature of Robert Hanssen: compartmentalization. I am a very experienced psychiatrist and Hanssen was the most compartmentalized person I have ever met. It means that he is capable of being a remarkably different person in terms of outlook, values and behavior at different times and circumstances, to the point of making me wonder whether he should be diagnosed with Multiple Personality Disorder. The actual existence of MPD is disputed, but even if it does, I don’t think Hanssen fits it. On the other hand, if there were a compartmentalization measure, Hanssen would be a 10 on a ten-point scale, whereas most of us would be down at a 1 or 2, which is totally normal, depending on what life situations or roles we happen to occupy from time to time.

Let me start by highlighting the main psychological feature of Robert Hanssen: compartmentalization. I am a very experienced psychiatrist and Hanssen was the most compartmentalized person I have ever met. It means that he is capable of being a remarkably different person in terms of outlook, values and behavior at different times and circumstances, to the point of making me wonder whether he should be diagnosed with Multiple Personality Disorder. The actual existence of MPD is disputed, but even if it does, I don’t think Hanssen fits it. On the other hand, if there were a compartmentalization measure, Hanssen would be a 10 on a ten-point scale, whereas most of us would be down at a 1 or 2, which is totally normal, depending on what life situations or roles we happen to occupy from time to time.

The program did a good job of portraying a number of the different Hanssens: Ambitious, hard-working, career-minded FBI Special Agent; victim of psychological abuse by his father; ardent lover of a beautiful woman, Bonnie, who became his devoted wife; good friend to a few co-workers; passionate Catholic who aligned with the secretive Opus Dei sect; engaged family man who was attached strongly to his six children; involvement with a stripper not his wife; and of course, a KGB mole. And all these diverse personas do not even complete the list.

The Reelz program showed me additional sides of Hanssen beyond what he presented to me, but nothing I saw fundamentally set aside my original take on him. For example, while I knew about his involvement with the stripper Priscilla Sue Galey, I didn’t know all the details mentioned in the show and I had never seen a photo or video interview of her.

I have to mention here that I got explicit permission from Hanssen to discuss his case publicly for the purposes of education, to help the intelligence community better understand the psychology of the insider spy—a loyal employee who turns bad. The only restriction he placed on me was not to discuss anything about Galey, and while I have been asked many times about this part of his story, I have abided by his restriction. That said, getting to see more about her in this program was a new thing for me, too.

Another thing made more plain to me was how abusive Hanssen’s father was to him over the course of his life. I did learn about Hanssen’s childhood memories of his father’s emotional abuse, because the very first story he told me was of his humiliation when, as a punishment, his father literally rolled him up inside a carpet. I didn’t know that over the years, into adulthood, his father, a Chicago policeman, never let up. His father belittled him when he joined the FBI, even on his wedding day, when he announced to his son’s soon-to-be-wife that she was marrying a loser.

Jack in the Box

I was taken aback by the willingness of Hanssen’s friend Jack Hoschouer to be interviewed for the program. A retired Army officer, Hoschouer was occasionally invited by Hanssen to watch the G-man and his wife having sex. That he was so candid in revealing his own complex and conflicted personality was astonishing. Back in the day, I spent more than five hours with Hoschouer and got a glimpse of a decent but tortured man who, years later, still couldn’t compute how he felt about his lifelong pal, a friend who drew him into behaviors about which he still feels shame. The program revealed even more about Hoschaur than I knew. I think he was brave to open himself up as much as he did.

The program also revealed details I hadn’t known about the conflict between Hanssen and his brother-in-law Mark Wauck, also an FBI agent (of all things), and Wauck’s supervisor Jim Lyle. Wauck says he developed his own suspicions that his brother-in-law could be a spy and attempted to warn the bureau. Lyle, however, recollects things differently, dismissing the accusation that he had ever been warned. A missed opportunity? That doesn’t fit the FBI’s number one rule: Never Embarrass the Bureau.

I had lost track of how many intervals appeared in Hanssen’s spying timeline, years in which the mole was dormant. There were about three periods that lasted for years within his 22-year-long spying career. I wrote about such dormancy in my white paper, Ten Life Stages of the Insider Spy, identifying it as Stage Seven. That was even before I met Hanssen. I had to be reminded how dramatic these periods were for him. My psychological explanation for dormancy, which I found occurred frequently with moles, is that it represents their fantasy-wish to turn back the clock and exit the quagmire they found themselves in. This was true for Hanssen, I believe.

The Spy Who Wasn’t

One hole in the program that was not unexpected but still galling: the story of the FBI’s hounding of Brian Kelley, a CIA officer who the bureau wrongly suspected of being the KGB’s mole. That painful episode got only passing mention in the show. It’s a sore spot for me because Brian was a dear friend of mine. The FBI, certain that Brian was their man, subjected not only him, but many members of his family, to intensive scrutiny, even harassment, for about three years. The idea that the mole was one of their own was beyond their comprehension. Their suspicions were initially aroused by Brian’s work on a sensitive counterintelligence case against the Russians that had gone sideways, but the topper was their discovery of a map Brian had of his jogging routes in a local park—routes that just happened to align with “dead drop” sites where Hanssen and the KGB exchanged secrets and cash.

To be fair, this was in the 1990s, a time when the CIA and FBI acted more as rivals than partners. The terror attacks of September 11, 2001 would change that dynamic, but it must also be said that the bureau was engulfed by an overdose of confirmation bias. All these years later, the episode remains painful.

Brian was eventually exonerated, but it took a terrible toll on him. He had taken the high road, going back to work without complaint, and he never sued the government for the terrible way he was treated. But it also wrankled him that he never got an apology from the FBI, and he poured out his pain to me for hours. A few short years later, in 2011, he died, way too young. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about Brian’s Shakespearian tale of tragedy. And now, with the release of the Reelz program, there’s still no word of a belated apology. He remains a footnote. That bothers me. Maybe Reelz should mount another thriller, “The Spy Who Wasn’t.”

The Actor Most Like Hanssen

I must also mention an anecdote brought to mind by the appearance in the program of one of Hanssen’s few real friends in the FBI, Paul Moore. I got to know Paul because we were both associated with David Major’s Counterintelligence Center, a private sector company that does training for the intelligence community workforce. On one occasion, based on my experience with Hanssen in jail, I was asked to give a talk to the Center’s staff and students about him.

I asked the audience to imagine casting someone to play Hanssen in a movie. As I started to name the actor that I thought could play him best, Paul shouted out from the sidelines, “Jeff Goldblum!” I was truly stunned: Goldblum—yes, he of Jurassic Park and so many other great roles—was the actor I was about to name. It was astonishing: Paul and I had not kibbitzed on it.

I asked the audience to imagine casting someone to play Hanssen in a movie. As I started to name the actor that I thought could play him best, Paul shouted out from the sidelines, “Jeff Goldblum!” I was truly stunned: Goldblum—yes, he of Jurassic Park and so many other great roles—was the actor I was about to name. It was astonishing: Paul and I had not kibbitzed on it.

Why Goldblum? In his many madcap roles, he’s always sharp and intellectual, as well as arrogant, precisely spoken, possessed of a wicked, droll, cutting sense of humor, eccentric, idiosyncratic, annoying—and hard to forget. Now, remember that I spent hours upon hours debriefing Hanssen. Paul Moore, an FBI analyst, had carpooled with Hanssen for years and considered him a close friend until the day he was arrested. Not to take anything away from Chris Cooper’s fabulous portrayal of Hanssen in the 2007 thriller Breach, but to Moore and me, who perhaps knew the turncoat best, Jeff Goldblum was the better choice.

Every February I have cause to remember Robert Hanssen—more so this year, the 20th anniversary of his arrest, when I was interviewed for not just the Reelz show but an episode of the SpyCraft series on Netflix devoted to his case. Until those broadcasts, however, I hadn’t realized that the day of Hanssen’s arrest, February 18, fell on my birthday. And that, it turns out, is just one of the surprises in the everlasting riddle of Robert Hanssen.